James Halliday on Monstrous Red Wines – McLaren Vale, Langhorne Creek and the Barossa are not favourites of the infuential wine writer. He made that clear in a speech some 18 years ago when he drew attention to the poor record of the trio at wine shows. Nine trophies in six shows for the trio combined compared with 22 for Clare, the Hunter Valley with 15, Coonawarra 13, Great Southern with 11, and the Eden and Yarra Valleys with eight each. Cross-regional blends accounted for eight.

Halliday commnted: “These three regions are overwhelmingly the birthplace of the monstrous red wines so beloved of [US wine writer] Robert Parker, yet they are also outranked by the Riverina (6), the King Valley (5), Orange (4) and the Grampians (4). Sorry, Mr Parker, whichever way you want to look at it, the Australian show judges profoundly disagree with you.”

I will look at what has happened since that study of trophies awarded at shows from 2000 to 2005 inclusive in another piece. Suffice it to say that the Halliday view has had great influence on the Australian wine industry. The full text of his speech in 2005 provides a good starting point for forming your own opinion.

“Thank You Mr Evans and Sorry Mr Parker”

Wine Press Club of NSW Annual Lecture by James Halliday

Delivered on 25 November 2005 at the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney, Australia.

Originally printed in Glug on Thursday, 8th December, 2005.

As an objective framework to a paper which necessarily has a large degree of subjective arguments and judgments, I decided I would start with an analysis of the trophy results for the last six Sydney Royal Wine Shows (from 2000 to 2005 inclusive). I looked at the varietal mix, the regional mix, and the winemaker mix, the first two simple enough, the last requiring some preliminary explanation.

So I will start with the winemakers. The primary division was between large, medium and small. I could give you a winery-by-winery classification, but – while some of you might disagree – the majority wouldn’t. When I considered the big company wines which had won trophies, I realised that many went to single vineyard or single region wines, invariably made in limited quantities (5000 cases or less, some much less). So I ended up with four categories: big company regional blends, 13 trophies; big company specific vineyard/region, 38 trophies; medium companies, 33 trophies; and small companies, 34 trophies.

I decided to exclude the various most successful exhibitor trophies, although there were some surprises (Margan Family twice in succession for premium current vintage), Yalumba and so forth. I also excluded fortified wines, which – if included – would have pushed the results even further to the limited production, region specific sector. It is difficult to say whether I was more surprised at the outcome of the regional or the varietal consensus. Suffice it to say my guesses would have been very wrong. Who would have thought that rieslings would have outgunned semillons – at the Sydney Wine Show, of all places – by 20 to 12, or that cabernet sauvignon would receive 27 trophies compared to the 17 for shiraz. Following in their wake came nine for sparkling wines, eight blended red trophies, seven for merlot, six for pinots, five for botrytised whites and two sauvignon blanc/sauvignon blanc semillon blends.

What About Chardonnays?

I can hear you asking why I have omitted chardonnays. Well, actually I haven’t; it is the judges who, in their infinite wisdom, have not awarded a trophy to chardonnay since 2000. In that year 1997 Houghton Crofters won a trophy, as did a wine selling for less than $15 called Endless Summer, which was presumably a chardonnay, although I am not sure.

My next point of examination was the regions represented by the trophy wines. Clare Valley was the clearest possible winner with 22, followed by the Hunter Valley with 15, Coonawarra with 13, Great Southern with 11, and the Eden and Yarra Valleys with eight each. Cross-regional blends accounted for eight.

But what about the McLaren Vale, Langhorne Creek and the Barossa Valley? Five for McLaren Vale and two each for Langhorne Creek and – amazingly for some – the Barossa Valley.

James Halliday on Monstrous Red Wines

These three regions are overwhelmingly the birthplace of the monstrous red wines so beloved of Robert Parker, yet they are also outranked by the Riverina (6), the King Valley (5), Orange (4) and the Grampians (4). Sorry, Mr Parker, whichever way you want to look at it, the Australian show judges profoundly disagree with you.

By chance, issue 161 of Parker’s Wine Advocate has just hit the airwaves here, underlining in various ways how small his Australian tasting base is compared to his ex cathedra pronouncements. Thus he says:

“One of the perennial criticisms of the South Australian wines is they are no more than one-dimensional fruit bombs that will fall apart with age – going back and tasting through the 1995s, 1996s and 1998s that were bestowed high marks proves time and time again that these wines, while approachable and drinkable young, have the balance, concentration and material to age for 20 years or more.”

On the face of it, no one could deny that wines from these very good vintages will age for even longer than the 20 years Parker proposes. But it ignores the fact that – for example – Grange seldom exceeds 14% alcohol, and as we all know, has a 40-year-plus life span. Good South Australian Shirazs and Cabernets which are medium-bodied, with alcohol levels of 14.5% or less, age every bit as well as the highly extracted, full-bodied wines of 15% to 16.5% alcohol. The only difference is that the former are easy to drink (and I mean drink, not taste) from day one, while the latter need a decade and a barbequed slab of rump steak.

The Parker View that Big is Good,Bigger is Better and Biggest is Best

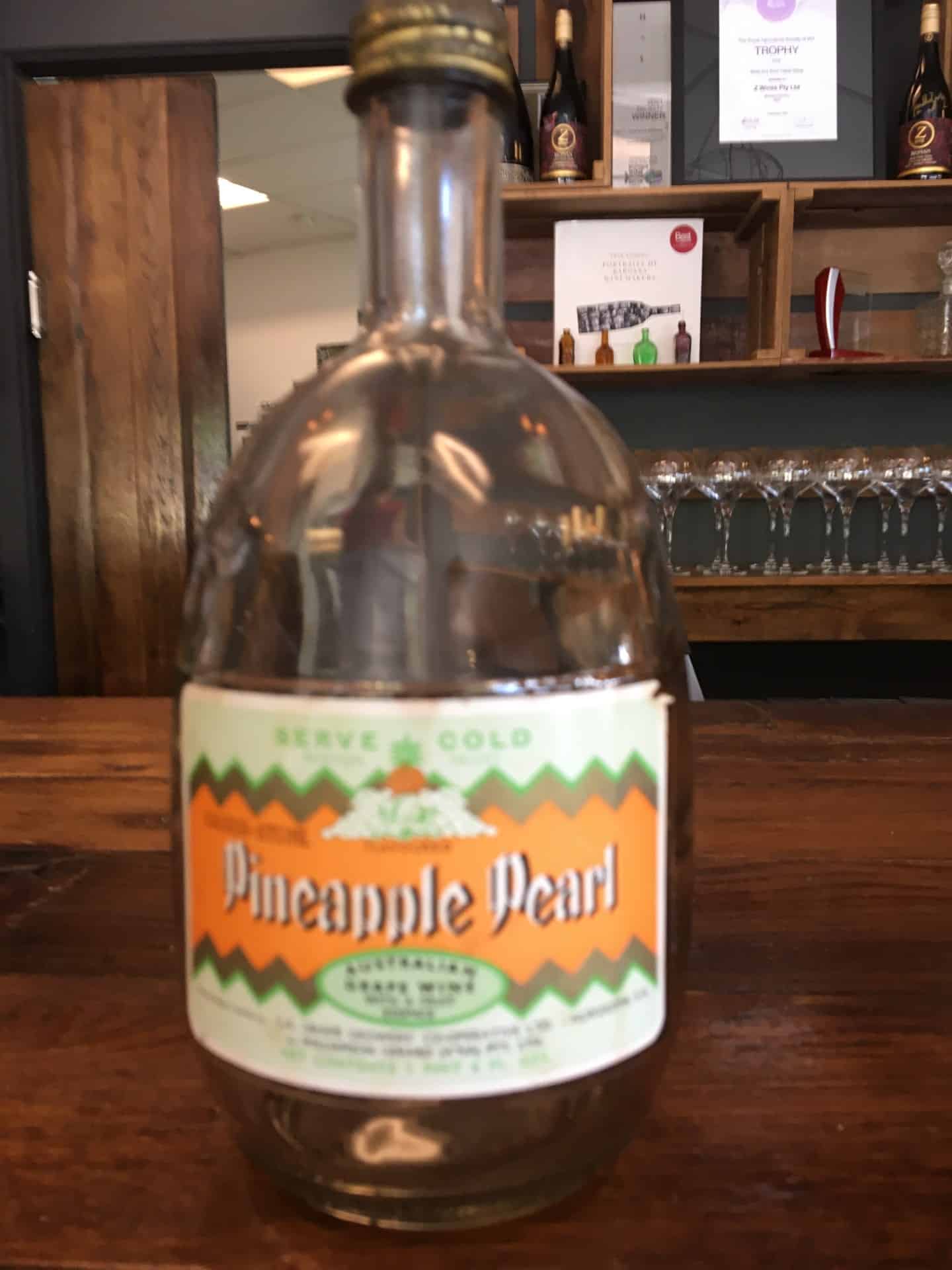

If, as is clearly the case, and irrespective of the country of origin, for Parker, big is good, bigger is better, and biggest is best, it comes as no surprise to read the following pearl of wisdom:

“This (the Yarra Valley) is Australia’s most fashionable viticultural area as well as the darling of the wine press. Its proponents (the provincial Australian wine press) argue that the climate and resulting wines come closest in spirit to those of Bordeaux and Burgundy in France. I am not convinced – there is much more ‘sizzle’ than substance for most wineries from Yarra Valley.”

I’m sure you will all appreciate our provincial nature and convict ancestry, but it would be nice if Mr Parker would refrain from judgements based on tastings of no more than ten per cent of the 120 Yarra Valley wineries. I also clearly wish he had blind tasted the 1990 and 1996 Quintets at the Len Evans Tutorials (in the company of great Bordeaux blends from around the world) which were consistently rated near the top by the 16 tutors and scholars (without any discussion). He might have thought twice before saying this:

“The proprietor of Mount Mary has never wanted me to taste his wines, which are revered by some segments of the Australian press, but with some stealth work, I was able to secure a few vintages. In addition to the 2001 Quintet, I was able to taste the 1998, 1997, 1995 and 1994. For my taste, only the 2001 merited a score higher than 80 points. The attempt appears to be to emulate our Bordeaux petite chateau, but none were as fine, being lean, high in acid, austere and meagerly endowed. They will not improve with age. The 2001 has slightly more to it than the older vintages. It is difficult to understand what merit these wines possess.”

It is quite apparent that the sustained auction demand for Mount Mary is some arcane conspiracy, because Dr John Middleton resolutely refuses to send samples of any of his wines to our provincial press. Either that, or the whole world is out of step with the Emperor of Wine. (As a postscript, Middleton does not acidify his wines, which are relatively low in acidity (under 6 grammes per litre). This is a perennial bug bear of Parker.)

Finally, I was amazed to read of the “enthusiastic acceptance of local wine consumers of unoaked chardonnays.” I must have missed the sound of one hand clapping. Before moving on, I should acknowledge Robert Parker also had this to say: “Another myth about Australian wines is that they will taste alike. Of course there is plenty of industrial crap that I wasted days tasting through, but the top-notch wines are dramatically different, even within the same viticultural regions. However, trying to portray Australia as some sort of monolithic wine producing region is a knucklehead attitude, and completely ignores the reality of actually tasting the wines, especially in the view of the diversity of Australian wine styles, even within the same region.”

I now wish to turn my attention to another well-known American winewriter and critic, who is – if possible – even more misguided than Robert Parker. But before I do so I should point out that virtually all the Hunter Valley trophies went to semillons, and the majority of the Clare Valley awards to rieslings.

These two wines are among the purest and simplest expression of variety and terroir you can find anywhere in the world. They are, it is true, profoundly misunderstood and largely neglected by writers, importers, distributors, retailers and customers outside of Australia. Moreover, most Hunter semillon is sold in Sydney, rather than elsewhere in the world. I will return to this issue later in this speech.

Giving the Wine Spectator a Serve

Matt Kramer, who writes a monthly column for the Wine Spectator, and who has been the champion of terroir in several books, most notably Making Sense of Burgundy, has visited Australia on a number of occasions, judging at the National Wine Show several years ago, and being the keynote speaker at the Mornington Peninsula Pinot Noir Symposium earlier this year.

There was a rumour, indeed, that he was contemplating living in the Adelaide Hills for six months each year, a rumour he flatly denied when I asked him about it at the Symposium. Both he and we should be grateful for that decision given the parting broadside he delivered as he left Australia.

Stripped to the essentials, he made three points:

(1) The big companies set wine style and benchmarks, not the small artisan winemakers.

(2) This style is validated by the wine shows where big company winemakers judge their own wines and engage in what he calls taste fixing.

(3) Most of the small producers don’t exhibit in the shows, nor do they become involved in wine judging.

I could simply point to the trophy analysis, and leave it at that, but that would be too easy. Looking first at the big company benchmarks, Grange leaps to mind. It is revered by virtually everyone who has had the good fortune to drink it, particularly when it is mature. This is a truly great wine, made in varying amounts from year to year, the amount decided by the small group of winemakers who fiercely protect the integrity of their inheritance. Neither corporate bean counters nor marketers have any say in the amount made or the cost of production. It is a pure accident that it is made by a big company.

Henschke’s Hill of Grace comes second in the shiraz category; no big company here, and neither it nor Grange are ‘validated” in wine shows, simply because they aren’t entered in the first place. From this point on there is a veritable explosion in the multiple styles of shiraz made from cool grown shiraz viognier blends (Clonakilla and Yering Station are foremost examples) to the controlled silky power of Best’s, Mount Langi Ghiran and Seppelt in the Grampians to the intensity and opulence of Jasper Hill in Heathcote to the sheer class of Wirra Wirra in McLaren Vale and ultimately to the home of old vine shiraz, the Barossa Valley.

There are so many makers of such diverse styles you would never reach agreement on benchmarks. Certainly Penfolds (RWT) and Blass (various, though by no means all from the Barossa) are at the forefront, but they are massively outnumbered by small producers new and old alike.

Many of these small producer wines are fairly and squarely aimed at the Parker palate, tipping the scales at 15$ to 16$, massively fruity, massively structured, and swathed in oak. The near-absence of Barossa Valley trophies is explained by two factors: most do not enter the show system, and those that do, have negligible success. It is, if you like, a simultaneous poke in the eye for Messrs Parker and Kramer alike.

The benchmark chardonnay in Australia is, in my view, Leeuwin Estate, although others would credibly argue for Giaconda, with Yattarna (small volume) in close attendance. Beyond these, small wineries from the Adelaide Hills, Margaret River, Yarra Valley and Geelong all produce beautiful, elegant Chardonnays.

All the top pinot noirs are made by small producers, which in turn utterly dominate wine shows. Few have attracted the Parker palate sufficiently to even merit a mention, and none provide any justification for Kramer’s jibes. With one or two exceptions, Australia’s numerous rieslings and semillons fall into the same basket.

The exceptions are Blass, Yalumba and Leo Buring (riesling) and Richmond Grove and Lehmann (riesling and semillon). I am sorry, Mr Kramer, not a scintilla of taste fixing.

Finally, and briefly, I come to cabernet sauvignons and cabernet merlot blends. Simply because I couldn’t think of a clear leader in the cabernet sauvignon stakes – Penfolds Bin 707 is very good, John Riddoch likewise, but neither dominates – I turned to my 2006 Wine Companion. It lists the top-pointed wines on a variety-by-variety basis, an unexpurgated extract from the database. Five of the 18 wines scoring 95 points or above came from large companies (including, incidentally, Bin 707), 13 from small makers. The same pattern emerges with Bordeaux blends, notwithstanding the absence of Cullen Cabernet Merlot (one of Australia’s greatest examples) due to a gap between releases.

Before moving on I should acknowledge the absolute mastery of Hardys sparkling winemaker, Ed Carr. These wines are below the Parker horizon, and if Kramer can explain who taste fixing extends to the multi-faceted Hardys sparkling wines, which rightly dominate the show system, I shall be most impressed and even more surprised.

The Issue of Show Judges

And so we come to the issue of show judges. In the years 2001 to 2005 inclusive, there were 65 judging spaces at the Sydney Show: in other words, 13 judges (including the Chairman) for each of the five years. The allocation was 18 for large company winemakers, three for medium companies, 14 for small wineries, 25 for winewriters/ academics/sommeliers/retailers, and five for overseas wine judges. First, Mr Kramer, please note the very significant participation of small company wine judges, more than half of whom do enter their wines in shows. Given that just under half the entire judging complement are completely independent, having no affiliations with any exhibitor, large or small, Kramer’s suggestions of big company taste fixing are farcical.

At the same time, the composition of the judging panels goes a long way to explaining why Parkeresque wines seldom achieve any significant recognition. Under the Chairmanship of Brian Croser, there has been an emphatic instruction to all judges to reward wines with finesse and elegance, and to penalise over-ripe, over-extracted wines. I can assure you there will be no change of policy under my forthcoming Chairmanship.

Which brings me to the future. Thanks to the annual Len Evans Tutorials, 12 relatively young wine professionals from various parts of the industry are given an immersion-bath in great wines of the world over a five-day period. It is not for the faint-hearted, nor for those without a good grounding in fine wine. In the mornings 30 wines of a given variety – chardonnay, pinot noir, shiraz and cabernet/cabernet blends – are tasted and judged under wine show conditions, ie. in absolute silence. All the scholars (as they are called) know is that all or some of Australia, France, Italy, California and New Zealand are represented, and that there will be a span of at least 20 years, the vintages normally jumbled up. The tasting takes an hour; thereafter each student calls his or her points for each wine, and are called on to explain why he/she gave those points.

The five tutors taste the wines at the same time as the scholars, and go to an outside room to call their points, only Evans having been privy to the identity of the wines. There is in fact seldom much disagreement, and the points are simply averaged. It is against this average that the points of the students are compared; normally a deviation of more than one point will result in an error being recorded. However, if there is a similar split between tutors and students alike, no penalty will be recorded.

The afternoons are devoted to Masterclasses covering the greatest wines of France (including Germany in the case of riesling), a smorgasbord of Grand Crus and First Growths just for starters. In the evening, over a three-hour dinner, there will be masked flights of wines for discussion and recognition via various forms of the Options game, interspersed with single options wines with the classic five-question, multiple option format.

The 12 scholars (selected from 100 or so applications each year) have provided an incredibly rich pool of young talent, and all of the associate judges at the Sydney Wine Show for the past three years have come from the cream of the Tutorials, Canberra likewise.

When I say young I have to remember that when I was 18, anyone over 30 was old, very old. Now, anyone under 35 is young, under 30 positively youthful. So when I say the Tutorials have caused me to embark on a youth policy at all the nine shows I chair or cochair each year, you may wish to mentally qualify my policy description. Nonetheless, the progression through the wine show judging hierarchy from associate to judge to panel chair is far more rapid than it used to be, and those selected have a much greater knowledge of the great wines of the world (which are yardsticks for Australian wines) than previously.

What I might cheekily, but I hope not smugly, describe as a worldview had its genesis in the second half of the 1970s, when Len Evans began the tradition of judges (and associates) dinners during the currency of the Show. It was also the time that Australian flying winemakers first spread their wings in earnest, and I would like to think this was no coincidence. Thank you, Len Evans.

Judging Without Fear or Favour

So where are we now? With wine shows in Sydney, Canberra and Adelaide which are judged without fear or favour by panels of three with either none or one big company judge who, in any event, would vigorously reject Kramer’s assertions of taste fixing. They bring vast experience and integrity to the process, and must always be part of a vigorous and proactive show system.

What, then, about Robert Parker? Well, while many of us baulk at the Parker red wine style, we must remember that these wines have an avid reception from influential and wealthy wine connoisseurs. Moreover, thanks to a combination of old vines, climate/terroir and skilled winemaking, we can create and sell these wines for far less than their Rhone Valley counterparts, such as the super-cuvees of Guigal.

The real challenge is to persuade Parker et al that mature Hunter semillon, and top-flight dry riesling, young or old are as great as they are unique. Likewise, while not unique, the white Bordeaux style semillon sauvignon blancs of the Adelaide Hills, Margaret River, Eden/Clare Valleys, Great Southern and Tasmania are of world class.

We make sophisticated wines, but we have failed to market these with any concerted degree of sophistication. The French have had 300 years (Bordeaux) to 700 years (Burgundy) in which to accumulate sophisticated marketing know-how. Daunting though it may seem, we have to bridge that gap.

The need is obvious; the means of achieving it less so. Wine quality can always be improved, and will be as the plantings of the last ten years begin to mature and the legion of younger, quality-obsessed winemakers gain more and more experience. Without wishing to encourage complacency, the quality is there.

The problem is persuading the millions of consumers of Australian wines around the world to look beyond the horizons of yellowtail et al. The distressing fact is that exports of Australian wines costing more than $100 FOB per case have declined in volume over the past two years, while total volume has continued to soar.

It is hardly rocket science to observe that marketing dollars are needed if the trend is to be reversed. The problem is that, without exception, the big exporters are all focused on their premium wines which, in the slightly arcane language of marketing, means wines selling for less than $AUD15, $US5 or $US10. The ultra-premium wines in their portfolios, and all the big companies have these, are seen as irritating distractions in export markets, and as often as not sold as loss-leaders in the domestic market.

The small to medium-sized companies are to a lesser or greater degree much more dependent on ultra-premium wines. But while the spirit may be willing, the financial flesh is weak. Indeed, in a recent paper, Paul van der Lee persuasively argued that smaller high quality producers had a better chance of growing sales within Australia than without.

The one response from the captains of the wine industry has been to emphasise the very point which Parker concedes: the rainbow diversity of regional styles with which we are blessed. Region-based co-operative marketing is not a new concept, but may be the best option we have.